Honey Hokum

Humans have been suckers for its magical powers since we dwelt in the cave

Vogue magazine no longer has a regular place in this household, since our daughters saw through the fashion business and turned their backs on the whole racket. However, a kindly reader of this blog recently alerted me to some pages in the current issue of Vogue which she suspected might take my interest. She was right, not least because I reckon they could have been published intact in Thebes in 2025 BC.

Enthusing about the therapeutic benefits of “the sticky and sugary staple crafted by bees”, Vogue says, “From acne and dryness, to off-kilter pH and uneven skin tone, a topical application of honey may be your golden ticket to an improved complexion.”

(Memo to self: must check for off-kilter pH)

“For a makeshift mask,” the article recommends that you try “mixing honey with yoghurt, oatmeal, or clay before application, and rinsing thoroughly with a gentle exfoliant or cleanser.”

It’s easy to imagine that a fashion-minded young woman in ancient Memphis might have daubed something like that potion on her face before bed, rising early in the morning to wash it off with water drawn from the Nile before anybody could see her and take fright.

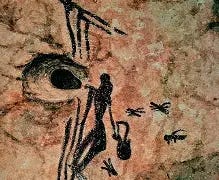

We know from the fossil record that bees and their honey date from at least 100m years ago, while the earliest fossil record of homo sapiens is only about 350,000 years old. Humans have been stealing honey from bees, however, since before they learned how to write. Cave drawings from the Cuevas de las Arana near Valencia, dating from about 8000 years ago, clearly show a half-naked woman climbing ropes to extract honey from bees’ nests high in trees (God help her). A relief in the sun temple at Abu Ghurab, dating from about 2500 BC, shows beekeepers attending hives, blowing smoke to calm the bees and then pinching the honey.

Meanwhile, for as long as they have been collecting honey, human beings have been attributing magical properties to the sticky and sugary stuff

Vogue listed the supposed health benefits of honey as follows:

Antibacterial and wound-healing properties: Honey, especially medical-grade varieties like Manuka, has natural antibacterial effects. It can help treat minor burns, cuts, and ulcers by keeping wounds moist and creating a protective barrier against infection.

Cough and sore throat relief: A spoonful of honey can soothe irritation and reduce coughing, particularly in children. It’s often more effective than over-the-counter cough suppressants.

Rich in antioxidants: Honey contains flavonoids and phenolic acids, which help neutralize free radicals in the body. These antioxidants may reduce the risk of chronic conditions like heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Supports digestive health: Honey’s antimicrobial properties can help with certain digestive issues, including gastritis and ulcers caused by Helicobacter pylori. It may also act as a prebiotic, supporting healthy gut bacteria.

Potential anti-cancer effects: honey may interfere with cancer cell growth by modulating immune responses and oxidative stress, though more research is needed in this area.

Improved blood sugar regulation: While honey is still a sugar, it may have a gentler effect on blood glucose levels compared to refined sugar, thanks to its antioxidant content. Still, moderation is key—especially for people with diabetes.

None of those claims appears to be backed by science but few would have been news to the first physicians who ever trafficked in potions, not long after humans emerged from the caves.

Honey was a staple in wound treatment in ancient Egypt. Egyptian papyri, like the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, describe honey being applied to open wounds and ulcers, especially for horses. Hippocrates recommended precisely the same prescription in Greece around 400 BC. Similarly, Roman and Islamic veterinary texts often included honey in salves for the treatment of wounds in cavalry horses.

It seems unlikely that such a rooted belief would cross so many civilisations and centuries without containing some verifiable truth but, at the same time, elements of animism, fetishism and talismanic magic are clearly evident in beliefs about honey that have passed down through millennia Whatever may be claimed for the therapeutic benefits of royal jelly, for instance, it is obvious that a lot of people go doolally over the stuff. That evidently includes the British Royal Family.

Royal jelly is the nutrient-rich, milky secretion produced from glands in the heads of nurse bees in the colony. It’s essentially the superfood of the hive, used to feed all bee larvae for the first few days of life—but only future queen bees are fed royal jelly exclusively and continuously, which is what triggers their transformation into queens.

With their superstitious weakness for homeopathic remedies and off-the-wall health fads, the British Royal Family has long had a thing about royal jelly. The late Queen Elizabeth was reported to take a daily hit of the stuff as long ago as the 1950s and the present King’s enthusiasm for alternative medicines has been one of his persistent oddities. Princess Diana was said to have taken royal jelly during her pregnancies to ward off morning sickness. The fact that this family’s standard of education has been around the level of cave-dwellers for generations and that the nearest thing they have produced to a scientist was Prince Philip with his naval training and his enthusiasm for gadgets may have some bearing on these habits.

They’re not the only ones. A couple of years ago, the Scottish Beekeepers’ Association gave airtime to an online talk called “An Introduction to Apitherapy” in which the speaker described the hive as “the world’s oldest and healthiest pharmacy”.

Among the health-giving benefits of royal jelly, she claimed:

Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects: Royal jelly contains unique proteins and fatty acids that may help reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, which are linked to many chronic diseases.

Cholesterol and heart health: may help lower total and LDL (“bad”) cholesterol levels, potentially reducing the risk of heart disease.

Immune system support: enhances immune response, possibly helping the body fend off infections more effectively.

Blood sugar regulation: may improve blood glucose control, which could be beneficial for people with type 2 diabetes.

Cognitive and neurological support: may improve memory and protect against neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer’s.

Fertility and hormonal balance: has been linked to improved sperm quality and hormonal regulation.

So it would appear that if you get enough of this stuff, you will never die – as Queen Elizabeth II, her mother and her husband all pretty much proved.

I am wary of every word of these claims. To my mind, it all seems too much like Theosophy or Freemasonry (irrational enthusiasms which have also had their adherents in the British Royal Family). The scientific research simply does not exist in sufficient strength to support any of these claims convincingly.

However, there is a cottage-industry business round my way which markets a “Bahooki cream” for sore bums which contains honey among other ingredients and is said to work wonders. That one I can fully believe - not least because I suspect they translated the recipe from cuneiform tablets found at Ur of the Chaldees.

Of course, that half naked Spanish girl might have simply been an early way of selling a product.

What is propolis?